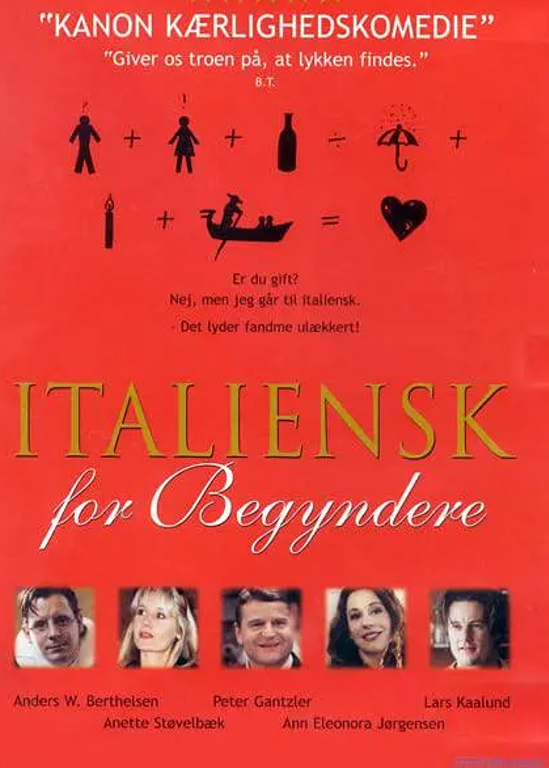

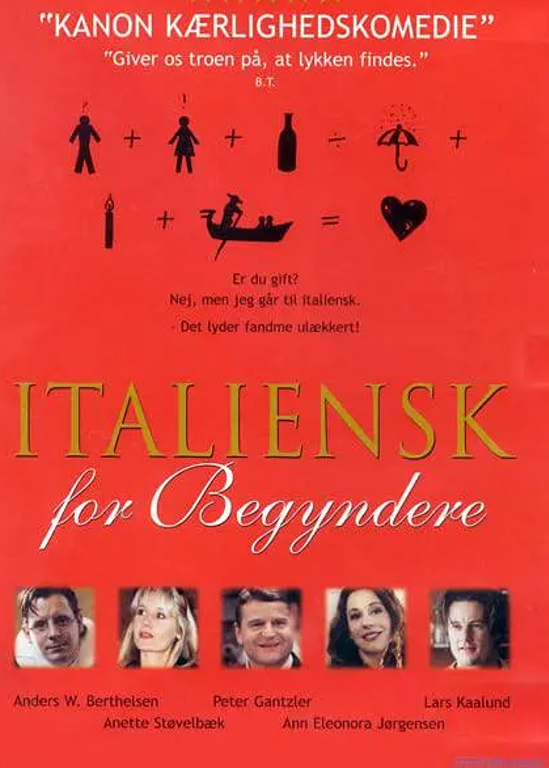

“Italian for Beginners”: A Delicate Tapestry of Human Connection and Resilient Joy

Lone Scherfig’s Italian for Beginners (2000) is a cinematic gem that defies categorization. Often labeled a romantic comedy, this Danish film transcends genre conventions to craft a tender, observant portrait of ordinary lives intersecting through shared vulnerability and the quiet courage to rebuild. Shot with handheld intimacy yet devoid of pretension, Scherfig’s breakthrough feature—the first Dogme 95 film directed by a woman—masterfully balances life’s inherent sorrows with irrepressible humor, proving that lightness need not trivialize depth. Through interwoven narratives of six lonely souls navigating grief, insecurity, and the awkward beauty of second chances, the film becomes a testament to the transformative power of human connection, language, and small acts of courage.

Narrative Architecture: Six Lives, One Chorus of Hope

The film’s ensemble cast—a mosaic of early-thirties singles from divergent walks of life—converges at a community Italian class, a seemingly mundane setting that becomes a sanctuary for emotional rebirth. Scherfig avoids melodrama, instead opting for gentle realism as she unravels their stories:

- Andreas (The Grieving Priest): Newly arrived in town after a crisis of faith, Andreas (Anders W. Berthelsen) carries the weight of his father’s recent suicide. His gentle demeanor masks a quiet desperation to reconnect with life. A hotel waiter’s offhand suggestion leads him to the Italian class—a decision that becomes a lifeline, both linguistically and emotionally.

- Olympia (The Daughter of Secrets): Played with aching vulnerability by Anette Støvelbæk, Olympia is adrift after her abusive father’s death. A letter summoning her to the funeral of a mother she never knew unravels her fragile identity, revealing a half-sister, Karen, and a buried family history of alcoholism and neglect.

- Karen (The Resentful Caregiver): As the town’s brusque hairdresser (Ann Eleonora Jørgensen), Karen has spent years nursing her alcoholic mother, her bitterness a shield against emotional exhaustion. Her mother’s death liberates her but leaves her untethered—until an impulsive romance with Giulia, a fiery-tempered waiter, sparks tentative hope.

- Giulia (The Fiery Teacher): A restaurant worker turned Italian instructor (Sara Indrio Jensen), Giulia’s journey from dismissed employee to unlikely mentor mirrors the film’s theme of reinvention. Her relationship with Karen—marked by clashes and unexpected tenderness—challenges both women to shed emotional armor.

- Hal-Finn (The Wounded Charmer): The hotel waiter (Lars Kaalund), whose sexual dysfunction following a sports injury has eroded his confidence, embodies the film’s delicate handling of male vulnerability. Unaware of the kitchen assistant’s secret affection, his bravado masks a fear of intimacy that slowly unravels through Italian class camaraderie.

- Lena (The Silent Admirer): Played by Anette Støvelbæk in a dual role, Lena—the Italian-Danish kitchen assistant—epitomizes quiet longing. Her enrollment in the class to pursue Hal-Finn adds a layer of poetic symmetry: just as language becomes a bridge for others, her gestures of love (a carefully packed lunch, shy smiles) speak volumes beyond vocabulary.

Language as Metaphor: Grammar of the Heart

Italian, for these characters, is more than a linguistic pursuit—it’s a metaphor for emotional risk-taking. The classroom scenes hum with unspoken tension: mispronounced verbs become opportunities for laughter; hesitant phrases crack open guarded hearts. Scherfig contrasts the rigid structure of grammar (“Conjugating love—amare—is easier than practicing it,” Andreas muses) with the messy reality of human relationships. When the class travels to Venice—a city built on water, fluidity, and romance—language barriers dissolve into shared wonder. The trip culminates in a restaurant scene where halting Italian, clinking glasses, and Ennio Morricone-esque music coalesce into a symphony of belonging.

Dogme 95 Nuances: Raw Aesthetics, Polished Humanity

As a Dogme 95 film, Italian for Beginners adheres to the movement’s minimalist tenets—natural lighting, handheld cameras, location shooting—yet subverts its often-grim associations. Scherfig’s camera doesn’t fetishize chaos; instead, it observes with compassionate stillness. Close-ups linger on micro-gestures: Karen’s trembling hands as she cuts hair, Hal-Finn’s defeated slouch after a failed date. The visual restraint amplifies emotional authenticity, making moments of connection—a brushed shoulder, a conspiratorial grin—feel monumental.

Notably, Scherfig diverges from fellow Dogme directors like von Trier (The Idiots) or Vinterberg (Festen), whose works often wallow in despair. Here, even grief has a wry humor: Olympia’s disastrous attempt to cook her father’s funeral dinner (a hilariously charred casserole) becomes a catalyst for community, as classmates rally to share food and stories. Death looms—parents die, relationships crumble—but Scherfig insists on life’s stubborn joy.

The Alchemy of Contrasts: Heavy Themes, Light Touch

The film’s genius lies in its tonal balance. Sexual dysfunction, parental neglect, and existential doubt are treated with neither glibness nor melodrama. Consider Hal-Finn’s subplot: his impotence could easily veer into crude humor or pathos. Instead, Scherfig mines it for empathetic comedy. In a standout scene, he practices seduction lines in Italian—”Il tuo sorriso è come il sole” (“Your smile is like the sun”)—only to trip over a chair, deflating his machismo. Yet when Lena later whispers the same phrase to him, the clumsy words transform into a healing balm.

Similarly, Karen and Giulia’s romance avoids cliché. Their first kiss, set against a drab parking lot, is awkward and sweet—a far cry from Venetian gondolas. Scherfig suggests that love isn’t found in grand gestures but in shared vulnerability: Giulia admitting her fear of teaching, Karen confessing she’s never left Denmark.

Venice: Mirage or Mirror?

The Venetian finale, drenched in golden light and operatic romance, risks tipping into fairy-tale contrivance. Yet Scherfig grounds the escapade in human imperfection. Andreas, clutching a phrasebook, botches a declaration to a widowed baker; Olympia, overwhelmed by the city’s beauty, bursts into tears at a café. Venice isn’t a magical cure but a mirror, reflecting back the characters’ capacity for wonder. When they dance in a moonlit piazza—Hal-Finn swinging Lena in a joyous arc, Karen and Giulia swaying cheek-to-cheek—the scene feels earned, a reward for their collective courage to embrace life’s “dolce far niente” (sweetness of doing nothing).

Legacy and Conclusion: Quiet Revolution

Over two decades later, Italian for Beginners remains a quietly revolutionary work. Scherfig’s female gaze infuses the narrative with uncommon empathy, particularly toward male fragility (Andreas’ gentle sorrow, Hal-Finn’s bruised ego). Her direction champions subtlety over spectacle, finding poetry in a language workbook’s dog-eared pages or the steam rising from a shared espresso.

In an era obsessed with hyperbole, the film’s power lies in its modesty. These characters don’t “find themselves” in Italy; they simply permit themselves to be seen. As the closing credits roll—over a sunlit Venetian canal and the strains of Puccini—we’re left with a lingering warmth, a reminder that joy isn’t the absence of pain but the choice to whisper “ancora” (again) to life, one imperfect verb at a time.

Italian for Beginners is more than a rom-com; it’s a masterclass in resilient hope—a film that, like the best language lessons, teaches us how to say “yes” when the world expects “no.”