Deconstructing Moral Hypocrisy: A Critical Examination of Female Agency in “O Primo Basílio”

Eça de Queirós’ 19th-century novel adapted into various screen versions presents a fascinating case study in moral ambiguity through its protagonist Luísa. This analysis seeks to challenge conventional sympathetic readings of the character by dissecting the psychological complexity and ethical contradictions underlying her actions. Far from being a simple victim of patriarchal oppression, Luísa emerges as a compelling study of self-deception and calculated self-preservation.

The Anatomy of Infidelity: From Opportunism to Hedonism

The narrative trajectory of Luísa’s affair with her cousin Basílio reveals a calculated progression rather than impulsive passion. Initially framed as escapism from her monotonous marriage to engineer Jorge, the affair’s development exposes deeper layers of moral compromise. What begins as a performative rebellion against bourgeois respectability (“marriage’s fake propriety” in her perception) evolves into unapologetic hedonism. Crucially missing from her psychological journey is any substantive moral reckoning – her primary concern remains the maintenance of social facade rather than authentic guilt.

The mechanics of her deception prove particularly telling. When confronted by her blackmailed servant Juliana, Luísa’s panic stems entirely from exposure anxiety rather than remorse. Her immediate solution – attempting to elope with Basílio – demonstrates transactional pragmatism. This proposed abandonment of her husband contains particular psychological violence: she plans to inflict maximum emotional damage through sudden disappearance while maintaining self-justifying narratives about “following love.”

The Paradox of Declared Affection

Most perplexing is Luísa’s persistent proclamations of spousal devotion post-affair. After Basílio’s abandonment, her renewed emphasis on loving Jorge creates cognitive dissonance. If her marital commitment were genuine, multiple ethical alternatives existed: voluntary confession, discreet separation, or even self-imposed exile. Instead, her actions follow a pattern of damage control – seeking lawyer Leopoldo’s help to contain the blackmail crisis while reiterating spousal attachment as emotional insurance.

This contradiction reaches its zenith in her deathbed declarations. The protagonist’s final words emphasize devotion to Jorge, yet this belated sentimentality rings hollow against her established behavioral patterns. One must question whether this represents genuine repentance or last-minute image curation – a final attempt to control her narrative legacy.

Self-Deception as Survival Mechanism

Luísa’s psychology reveals a masterclass in cognitive dissonance management. Her declaration that “for love, everything becomes innocent” functions as both romantic justification and ethical loophole. This convenient philosophy enables simultaneous exploitation of marital security and adulterous excitement. The crucial unspoken premise is that “love” here refers entirely to self-love – the preservation of her comfort, social standing, and access to passion.

Her approach to crisis management further illustrates this self-centered worldview. When blackmailed, she immediately seeks male intervention (Leopoldo) rather than confronting consequences personally. When abandoned by Basílio, she pivots to reinforcing her wifely role rather than examining her actions. Each choice prioritizes self-preservation over moral accountability.

Comparative Analysis: Luísa vs. Literary Adulteresses

Contextualizing Luísa within literary tradition highlights her unique moral positioning. Unlike Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina (genuine passion leading to social ruin) or Flaubert’s Emma Bovary (romantic delusion ending in self-destruction), Luísa displays calculated pragmatism. Her affair combines strategic advantage (Basílio’s Parisian sophistication vs Jorge’s bourgeois stability) with thrill-seeking. The absence of maternal instincts (her childlessness being notable) removes traditional feminine motivations, sharpening focus on self-interest.

Socio-Historical Context: Femininity as Performance

Set against Portugal’s 1870s social conservatism, Luísa’s actions gain additional complexity. While the novel critiques patriarchal oppression through female confinement to domestic spheres, Luísa subverts victimhood narratives by weaponizing femininity. Her manipulation of Jorge’s trust, Basílio’s lust, and Leopoldo’s chivalric instincts reveals agency through calculated performance of vulnerable femininity.

The famous scene where she packs her elopement trunk exemplifies this duality – performing romantic desperation for Basílio while practically ensuring financial preparedness (Jorge’s money). This juxtaposition of emotional theatrics with pragmatic planning underscores her survivalist mentality.

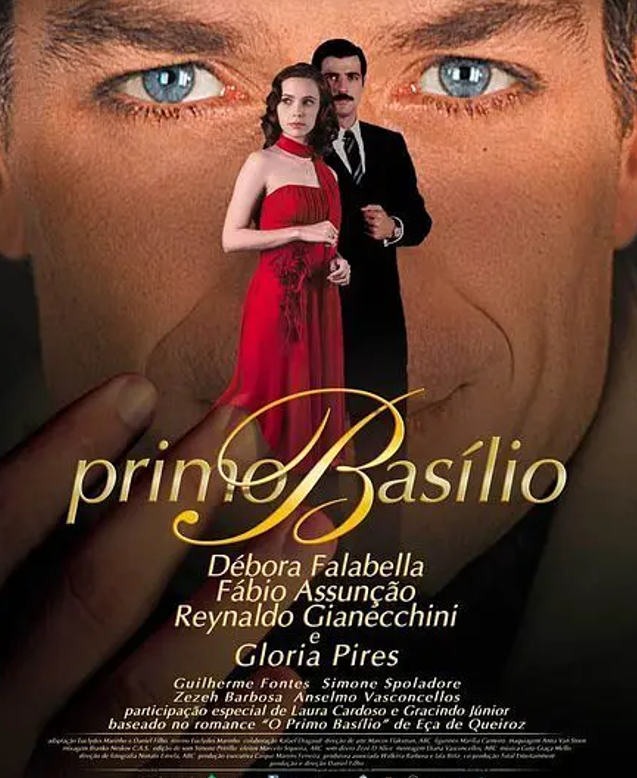

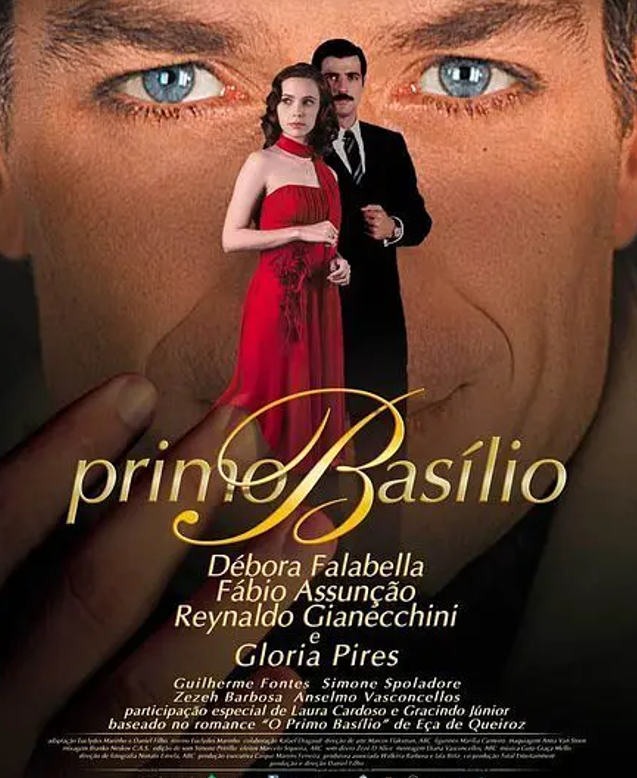

Cinematic Interpretations: Directorial Complicity in Whitewashing

Many film adaptations (notably 2007 Portuguese version) soften Luísa’s edges through sympathetic cinematography – lingering close-ups on anguished expressions, melancholy musical cues, and omission of her more calculating monologues. This directorial mediation creates false pathos, transforming what原著 presents as moral study into conventional melodrama.

A faithful adaptation would emphasize the cold precision of her actions: the deliberate timing of trysts during Jorge’s absence, the strategic tears deployed during confrontations, the careful maintenance of domestic normalcy between affairs. These behavioral patterns suggest not passionate abandonment but controlled duality.

Ethical Calculus: Self-Interest vs. Societal Expectations

Luísa’s ultimate tragedy stems from miscalculating risk rather than moral failure. Her psychological breakdown following exposure threat reveals not guilt but panic at losing social capital. The famous letter-writing sequence – continuing correspondence with Basílio despite reconciliation with Jorge – exposes her addiction to duplicity itself. Like a gambler doubling down, she seeks to maintain both marital security and illicit excitement, believing she can indefinitely balance these opposing forces.

Conclusion: Beyond Redemption Narratives

The protagonist’s eventual demise (variously portrayed as consumption or overdose across adaptations) completes this portrait of moral evasion. Rather than confronting her actions’ consequences, she escapes through physical deterioration – the ultimate passive-aggressive refusal of accountability. Her death becomes not tragic catharsis but final act of self-absorption, denying Jorge any closure while ensuring her remembered as victim rather than perpetrator.

This analysis ultimately positions Luísa as precursor to modern anti-heroines – a complex study in self-rationalization that challenges audiences to confront uncomfortable truths about human capacity for ethical gymnastics. Her enduring relevance lies in embodying the universal temptation to recast selfish choices as romantic destiny, a psychological maneuver as prevalent today as in 19th-century Lisbon.

By rejecting sentimental interpretations, we engage more meaningfully with Queirós’ critique of bourgeois hypocrisy. Luísa’s story serves not as cautionary tale about female sexuality, but as timeless mirror reflecting humanity’s infinite talent for self-justification – making “O Primo Basílio” disturbingly contemporary in its psychological insights.